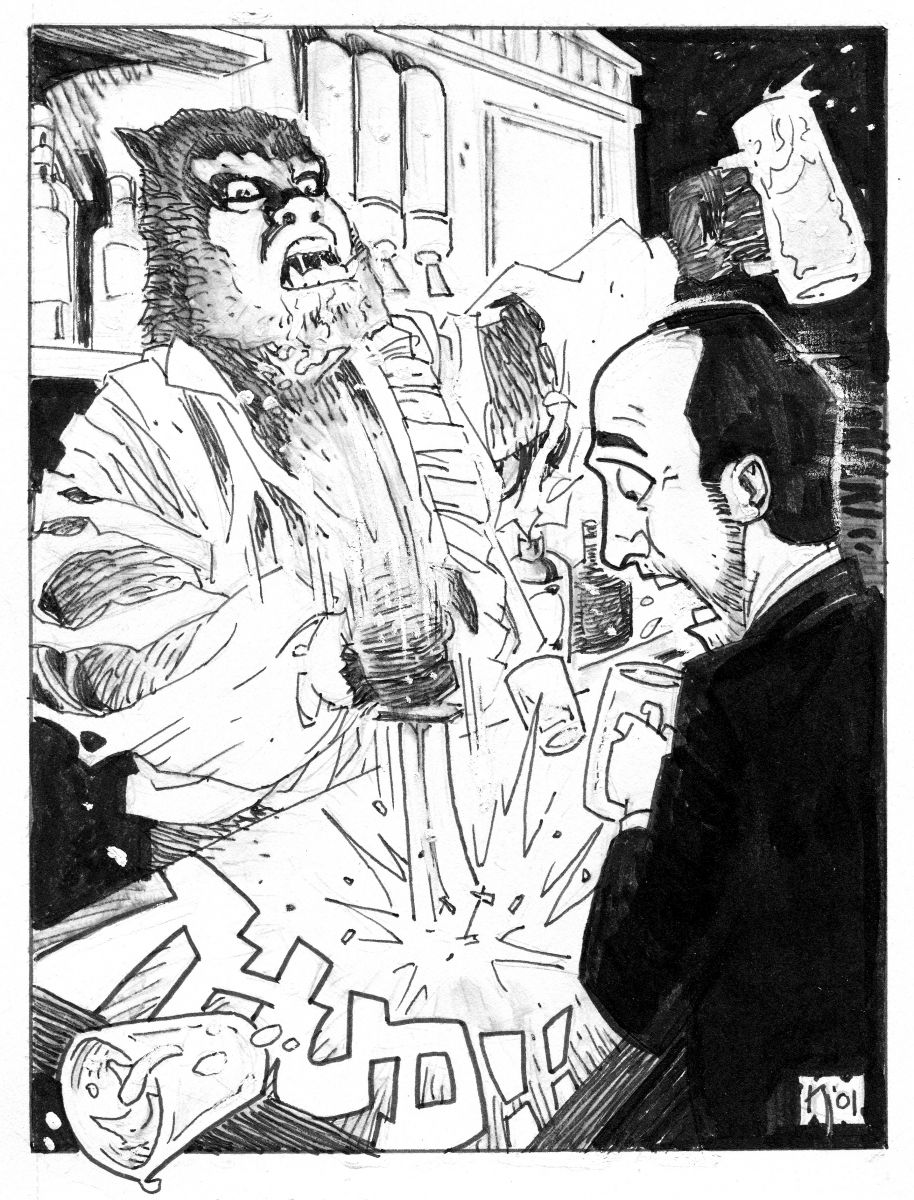

INTERVIEW WITH THE WEREWOLF

or; How Day Turned to Night in the Company of Oliver Reed

Oliver Reed was always destined to become an actor, despite his own version of events (in which he more or less ‘drifted’ into the profession) and with or without the timely intervention of Hammer Films.

Reed’s paternal grandfather was Sir Herbert Draper Beerbohm Tree - the most successful of the Victorian actor-managers, and half-brother to author Max Beerbohm. Like his contemporary, Henry Irving, at the Lyceum Theatre, Tree played all the great Shakespearian roles, but at the Haymarket in his case; he bought and ran Her Majesty’s Theatre in London in 1897, founded RADA (The Royal Academy of Dramatic Art) in 1904, and was awarded his knighthood in 1907. Tree’s wife, Helen Maud Holt, was herself an acclaimed actress, who played opposite her husband on many occasions and after his death (in 1917), went on to feature in several films as Lady Tree - most notably Alexander Korda’s The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933) and, in the year of her own death, The Man Who Could Work Miracles (1937), in which she had joined a cast that included Ernest Thesiger, George Zucco, and Torin Thatcher. The Trees’ eldest daughter, Viola, followed her parents onto the stage, as did her son, David.

In true Victorian style, however, Tree kept a mistress, and Beatrice May Reed also had children by him: Carol Reed was born in 1906, and he, too, became an actor, before a job as a dialogue coach with Ealing Studios led to a career as a director of films such as Odd Man Out and The Third Man and his own knighthood in 1952. Carol’s brother Peter, last of the five ‘Reed’ children, was born two years later, in 1908, and on February 13, 1938, his wife Marcia gave birth to their second son, whom the couple named Robert Oliver.

Robert’s father (a racing journalist), mother, and older brother David would remain unmoved by the call of the theatre. But for Robert Oliver Reed it was different: as family history showed and his restless nature was soon to confirm, acting was in his blood.

After a turbulent schooling and the obligatory two years of National Service spent in the Army Medical Corps, Reed first set foot on ‘civvy street’ in 1958 and began his working life in a variety of casual jobs.

Within a year, his brooding good looks and swaggering demeanour had brought him an audition with the BBC. There followed a series of walk-ons in films like The League of Gentlemen and His and Hers, and by the time of Beat Girl in 1959, Robert was gone and Oliver Reed was well and truly born. Next stop, Hammer - currently riding the crest of a wave of investment and popularity.

As luck would have it, Hammer house producer Tony Hinds was in the habit of switching available actors from one film to the next, to save time and money on re-recruiting for each new production. Reed was eminently available, and so a small but higher-profile role in The Two Faces of Dr Jekyll led quickly on to bigger and better things.

Reed’s breakthrough was swift. After Jekyll, Hammer’s next opus in the Gothic horror stakes was provisionally entitled ‘The Werewolf’, and as the lead role required gruelling hours in the make-up chair, it was thought to be better suited to an ambitious newcomer than an already established, and possibly more petulant, star. Reed’s surly and faintly brutish physiognomy appealed to Hammer make-up man Roy Ashton; he was given the job, but the rest is not quite history..

The Curse of the Werewolf, as the film soon became, put in a poor showing at the box-office in relation to Hammer’s previous horrors and Reed was again relegated to second-league status for the remainder of his nine outings with the company. In the meanwhile, however, his potential had been spotted by a young director called Michael Winner, who had now made a name for himself in the British ‘new wave’ with West 11. Having failed to secure Reed for that film, Winner managed to cast him in his next project, The System. It was the beginning of a beautiful friendship that lasted throughout the 1960s, and with it, Oliver Reed’s star was finally on the ascendant.

Oliver Reed was the last of the four actors I had desired to interview for my biography of Hammer, A History of Horrors. The other three - Cushing, Lee, and Michael Ripper had been chosen not just because of their lofty positions in the Hammer Hall of Fame, but because their careers with Hammer had spanned many films over a long period of time and the book was to be the story of the company itself, rather than a run-down of Hammer’s films per se. The four were thus in a unique position to have observed the changes that occurred in the personnel and operational methods of Hammer during those same periods. If I had been able to extend the time that I spent on researching the book, I would have added Michael Medwin to the roster.

Reed fitted the bill: his own career with Hammer Films had spanned a mere five years, but it had come at a critical period for the company, according to my timeline. If any further argument were needed, Oliver Reed was the only major mainstream star of international standing that Hammer ever produced. (And my wife liked him!)

At this point in time, Oliver Reed was more likely to be seen in the tabloid press, propositioning presenters on Sky News, or cavorting on television chat shows. His appearances on film had been few and far between, and mostly in features that went straight to video (though he still popped up in an occasional made-for-TV movie playing the heavy, as in Lew Grade’s production of Barbara Cartland's The Lady and the Highwayman, or Return to Lonesome Dove. Reed, by 1992 (when the prospect of interviewing him was first mooted), had become something of a legend in his own lifetime - and for all the wrong reasons.

Nevertheless, I decided at least to test the water. I had come upon Reed once before, at a press reception for The Devils, in 1971, when I was film critic for a local London newspaper. At the time, he was ‘Lord of the Manor’ at Broom Hall, a thirteenth century ‘pile’ near Dorking, in Surrey, and I had planned to go there to interview him. Unfortunately, events conspired against it.

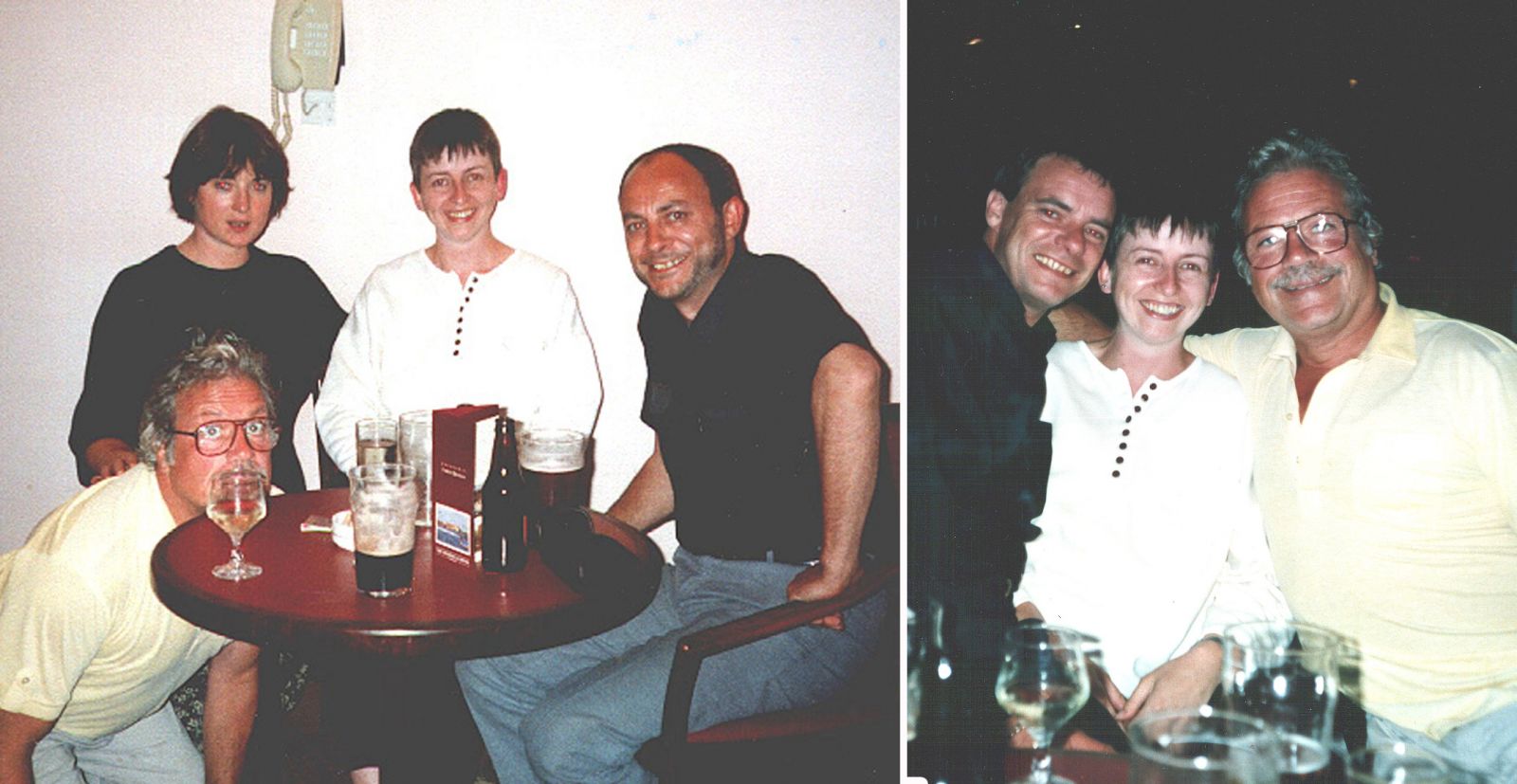

An approach was made reminding him of the occasion, and a series of faxes from Reed’s wife Josephine, acting on his behalf, took myself and my wife Jane, to Vale on the island of Guernsey - second largest of the four Channel Islands - where she and Oliver had lived in virtual tax exile since their wedding in 1985.

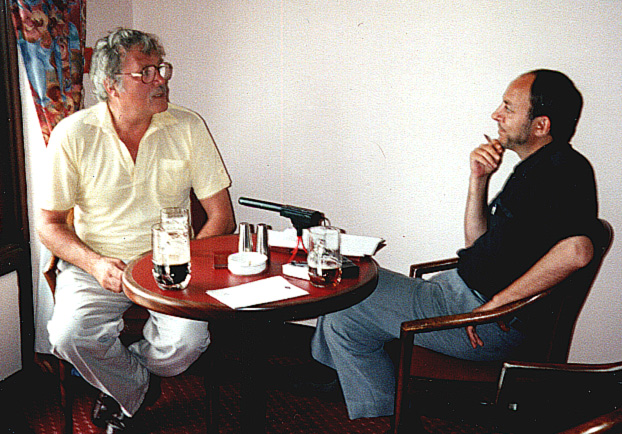

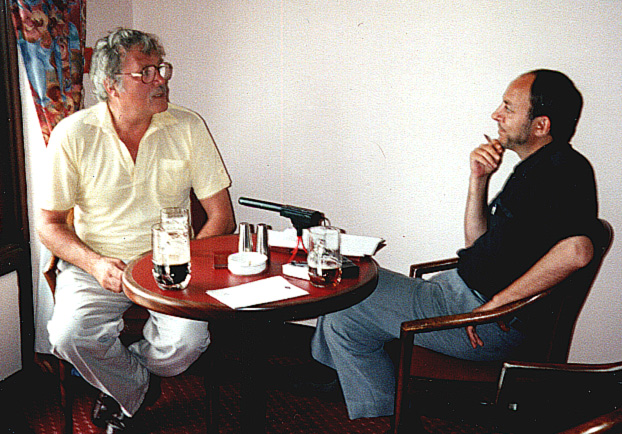

We had booked into the Peninsula Hotel - a great white elephant of a place, left over from the illusory boom of the Thatcher years - for two nights, and the interview was arranged to take place on the morning of the second day.. in the hotel bar (where else?).

At the duly appointed time of 11 a.m., Oliver arrived equipped with a companion - Jacko, by name - whose role in the proceedings, it soon emerged, was to ‘fag’ for the star. (For those unfamiliar with the novel ‘Tom Brown’s Schooldays’, ‘fags’ ran errands for the prefects.) Jacko was a ‘bag-man’, in Scorsesean vernacular, which in the case of Oliver Reed, meant that he was there to procure the alcohol.

This he duly did, and the three of us settled ourselves at a corner of the quiet bar to conduct the business at hand.

In appearance, Oliver was casually dressed and faintly unkempt, as though the process of sleeping and waking were a minor nuisance in a life of constant indulgence. But as if to belie this initial impression, he was politeness itself: courteous, complimentary, eager to please, and respondent to questions with patience and in that soft, mellifluous tone of voice which was as famous as his face. There was barely a trace of the roguish ‘Ollie’ Reed beloved of the tabloid press, though the shade of that other self could occasionally be glimpsed beneath the smile and the polished veneer of charm. ‘There was always some animal lurking under the surface,’ film director Ken Russell said of him.

To see the 54-year-old former boxer, bouncer, hospital porter, and film extra as he was in 1992 was nonetheless to be reminded of the more youthful Reed - the square-jawed, steely-eyed star of the sixties, who was loved by the camera and blessed with a presence on screen that had assured him international fame by the time he came to be cast as Father Urbain Grandier in Russell's film of The Devils. But I began, naturally enough, at the beginning. ‘How did it all start?’ I asked him.

‘I came out of the army and wanted to be an actor, so I went around lying to everyone that I'd been in rep [repertory theatre] in South Africa and Australia, because I didn't think anybody ever travelled to South Africa or Australia. One of the people I'd lied to was making a series for the BBC about Richard III and the Wars of the Roses [’The Golden Spur’] and I was cast as Richard. No one was more surprised than me because I'd never acted before in my life! - I'd been an extra in crowd scenes and the like, but I'd never acted. And one of the people who saw me in that was Stuart Lyons, who was then a casting director for Hammer Films.’

Reed went on to explain how a flair for theatrics had surfaced during his term at boarding-school - Ewell Castle School in Surrey - but two years National Service and a succession of menial jobs had followed his schooling, and the variety of eccentric occupations he had turned his hand to in an attempt to keep the ‘wolf’ from the door while he went the rounds of agents, producers, and casting directors in search of a break, had included working in a clip-joint in London’s Soho.

‘When I was working in the strip club, I had to wear a mackintosh, because all the fellows wanted to do was throw chocolate creams on the stage and let the girls dance on them, so it was rather messy. I used to put on the records and say, 'And now, gentleman, we have the lovely Yvonne.. But the girls I was looking after fired me; they were getting emotionally involved with me, so it wasn't very successful - you must never get emotionally involved with your clients..’

The BBC’s ‘The Golden Spur’ had led on to a handful of bit-parts in films. The Angry Silence, The League of Gentlemen, and Beat Girl had all required Reed to essay 'teddy-boy' types in line with his mean and moody good looks, and one French magazine had even gone so far as to christen him 'the British James Dean.' But none of these roles had meant more than a day or two's work at most.

‘I was about to go and sell washing machines, and the fellow who was interviewing me said, 'Of course, you know that sometimes you go and visit the ladies at lunch time, and they won't commit until the husband comes home at night, so you'll probably have to do a bit of 'the business' at lunch time while the husband's away - you don't mind that, do you?’ And I said, ‘No, I don't mind that at all’. But when I went back home to the flat, there was a phone call from Stuart Lyons and they had cast me in The Two Faces of Dr Jekyll. That was my first film for Hammer, in 1959, and it saved my bacon. (Stuart Lyons also tried to get me on Cleopatra in Rome, when he was casting director on that.)’

In The Two Faces of Dr Jekyll, Reed played yet another 'teddy-boy' type (Victorian on this occasion, despite the contradiction in terms) - and he was credited in the cast-list as the 'Strong Man’. But the mould was broken by a brace of beatnik roles in His and Hers and The Rebel, the first big-screen outing for small-screen comedian Tony Hancock.

‘After The Two Faces of Dr Jekyll, I went straight into The Rebel. The director [Robert Day] was a very well-known homosexual and I think he fancied me, and before I went off to see him, my wife wrote on my cock in biro, 'Leave it alone: he's mine'! When I went up to see him, I kept talking about my Uncle Carol [Reed], to let him know that my uncle was a film director and that if he dared so much as put his hand on my knee, I'd tell Uncle Carol - which I thought would be better than 'nutting' him..’

Reed encountered no such problems at Hammer, and when he next returned to the fold, he would stay for more than three years. ‘After I'd done The Rebel, I did Sword of Sherwood Forest.’

This was a retread of familiar greenwood territory for Hammer, who, six years before, had made Men of Sherwood Forest with Val Guest as director and Don Taylor in the role of Robin Hood. Sword of Sherwood Forest was a co-production with Richard Greene's Yeoman Films, and was designed as a spin-off from Greene's long-running TV series, ‘The Adventures of Robin Hood’. Reed’s role in the film, as the villainous Lord Melton, brought him into close contact with Peter Cushing for the first time - a little too close for Cushing's Sheriff of Nottingham, as it turned out, since he was to perish on the point of Melton's dagger! It was also Reed's second film for director Terence Fisher.

‘Peter would get more involved with Terry than I did. He was a very specific actor, who believed in writing everything down - 'I touch my hand, and I put my hand on the table, and then I point, and then I scratch myself..' He was so meticulous. Actors work in different ways.’

When Reed returned from Ardmore Studios in County Wicklow, in Eire, where Sword of Sherwood Forest had been filmed in the summer of 1960, his new employers were on the phone to him again.

‘Anthony Nelson Keys called me up (he was an associate producer at Hammer) and said, 'We're making a film called The Curse of the Werewolf - would you come and test for it?' And I said yes. That's the only test I've ever done in my life. I tested for the film with Catherine Feller, the girl with the little turned-up nose.. I remember going back on the train from Windsor with her..’

This time, it had been Terence Fisher who had suggested Reed for the role of Leon, after working with him on Sword of Sherwood Forest - and, perhaps, taking more than passing note of Dennison Thornton’s description of the character of Reed's hirsute medieval assassin in the press-book for the film: 'a scowl of thunder...a twisted soul...ready to murder at the drop of a visor'!

‘Terry Fisher was a wonderful gentleman who loved a little 'bevy' [a drink]. I found him very, very easy. I was a very nervous actor then, who'd done very little, and he just gave me my head.

‘My first two Hammers were done through Stuart Lyons, and then it was Tony [Keys]. On the Werewolf, I met Colin Garde, who was the make-up man, and Roy Ashton, likewise - who used to sing opera all the time! All the scenes with the make-up were done at once, because it was easier that way. It took a long time to put that stuff on and take it off and everybody used to piss off directly the bell went. They'd say, 'right, it's a wrap,' and everybody would go out and I'd just be left..’

Reed threw himself body and soul into the role of Leon Carido, the young Spaniard who is afflicted with the 'curse' of the title. And there were occasions during shooting when his exuberance got the better of him. And others.

‘I frightened the life out of little Michael Ripper in the prison scene, but I frightened Dennis Shaw [who played the jailer] even more, when I picked up that door and threw it at him. It wasn't a balsa-wood door - it was a real door (I was fitter in those days). And Dennis shat himself.. literally. He shat himself.’

Reed's fitness enabled him to tackle much of the stunt-work himself, including the running, jumping, standing-still chase sequence over the rooftops of 'Santa Vera' that occupied the cast and crew for two whole nights and served as the climax of the film.

‘Jackie Cooper did most of the more dangerous high stuff, but I did a lot of that running around in the square, and the scene where I was shot off the bell.’

Other reminiscences about The Curse of the Werewolf and Hammer in general were eventually incorporated into the relevant chapter of the book, and I see no need to repeat them here. When he was done with the film, Reed turned his attention to Bray Studios, and in common with most everyone else who ever worked there, his memories of Bray were suffused in a golden glow.

‘I didn't really know any other studios: all I knew was Lime Grove for the BBC, and Hammer. But it was just like a big family there, in that old house at Bray, right on the river. Absolutely super. Just one big, big family.

‘When I was making The Curse of the Werewolf, I was invited into the private dining-room to dine with the directors, which wasn't nearly as much fun as the canteen - especially as a werewolf - because all I could do was drink milk through a straw! Hammer used to make a film in a month, for £65,000 or something - it was extraordinary - though the actors saw very little of that..’

Nevertheless, it was enough, and Reed quickly became a 'regular' at the studio. He was well-regarded at Bray (especially by producer Tony Hinds, who thought him a ‘marvellous chap’) due to his desire to co-operate and his willingness to perform above and beyond the call of actorly duty.

‘I almost worked back-to-back with Hammer and, first and foremost, an actor's got to work if he's at all interested in acting. I gave them what they wanted: I knew my lines - I didn't knock over the furniture - I was on time. Working with Hammer taught me to know my lines, and hit my marks, and know exactly what I was doing. And do it quickly! It was very slick. It wasn't till later that I came upon people who really messed around and played the 'old madam.' Lighting men and the like. They'd say to me, 'see you later,' and you'd go away to your dressing-room for three hours while they lit a shot.. Hammer had a lot of very efficient people. After The Curse of the Werewolf, Joe Losey came along, and we made The Damned in May the following year.’

The Damned was directed by Hollywood 'exile' Joseph Losey (fresh from the success of The Criminal, with Stanley Baker, from an original screenplay by Jimmy Sangster). Losey was a maverick in more ways than one, and Hammer had been persuaded to use him by Columbia, the distributors of the film. Eager to promote its new ‘star’, Hammer insisted in return that Reed (as well as current ‘hot’ property Shirley Anne Field) be included in the package for box-office insurance.

‘Losey was one of those who had been chased out of Hollywood because of his associations with people who wanted to ban the bomb and who believed in socialism. He wasn't a communist; he just didn't believe in war. So he made The Damned, which was really anti-bomb - sort of 'look what we're doing; are we going to inherit the ashes of the earth?' He used to wear home-woven clothes. All his stuff looked as if it was made out of sackcloth and ashes. And it was all in olive green, and lovat green, and pale brown.. and hand-knitted ties. He was very generous; he used to take the cast out to dinner and preach anti-bomb stuff to them! He was very left of centre.. The last time I saw him was in the St Regis Hotel in New York, and then I found him extraordinarily arrogant because he had made these films that were successful. After The Damned, I did The Pirates of Blood River.’

Produced in the summer of 1961, The Pirates of Blood River finally paired Reed with Hammer's other star-name - Christopher Lee - with whom he had previously shared only a single scene in The Two Faces of Dr Jekyll. Lee would put his Mercedes at the disposal of the other members of the cast for the daily trips to the studio, 'entertaining' them by singing opera along the way.

‘I've never forgotten Christopher Lee. He was very sweet. He used to pick Dennis Shaw and myself up at Earls Court and drive us both down to Bray - and then he used to charge us for the petrol money! (He didn't really, but I always used to accuse him of it and he'd say, ‘No, I didn't - No, no!’) I've got a lot of time for Christopher - a lot of time; he's a very clever actor. I remember once when we were wading through all those bogs in The Pirates of Blood River.. Christopher's about six-foot-four so he could breathe, and anybody about six foot (like myself) could just about breathe, and poor little Michael Ripper - this little midget pirate - was so small that he was panicking all the time because he was nearly drowning! He was a great social mate of Tony Hinds, was little Michael.

‘There was another time when the stunt men wouldn't jump over a bank or something. I went charging over this bank with a sword in my mouth, followed by a medical student (who was one of the crowd) - and all the stunt men stopped; they wouldn't do it. And John Gilling, who was the director, fired them all. From that time on, he thought I was really quite something, because I'd do things that stunt men wouldn't do. It was only because I was stupid!’

A second 'pirate' adventure followed only one month after the first: Captain Clegg. ‘Peter [Cushing] gave me a good piece of advice on Captain Clegg - I was supposed to be wounded, and in actual fact, I'd just been in a crash - my wife had turned over a car - and on the very first day of shooting, I was this 'scarecrow' who's been shot, and someone had to come in, grab my arm, and say, 'Are you all right?'‘ [In the scene in question, this leads to the unmasking of the character.] ‘Anyhow, I winced, and said, 'Yes.. I'm all right.. I'm all right..' And Peter wrote me a letter afterwards which said, 'I think you're going to go a very long way, Oliver - but always remember: if you are hurt, you don't have to act hurt. If somebody grabs you, just blink. The screen is so big that even the slightest movement makes the point.' And from that time on, all I used to do was.. spit!’

‘I did a television play for Peter Graham Scott [director of Captain Clegg] in 1962, called ‘The Second Chef’, and he asked me to do quite a lot for him after that, but at the time, I didn't want to do too much television. [Reed did one more play for Scott - ‘Murder in Shorthand’, also in 1962.] He was very good to me. I remember falling in love with Yvonne Romain on that film..’

Columbia was unhappy with The Damned and it was temporarily set aside. As a result, Reed's Hammer work slowed down significantly in 1962 and he was only called on once, in July, to play opposite Janette Scott in Paranoiac. That year was the beginning of a troubled time for the company, and Paranoiac had been a rehash of an old screenplay for ‘Brat Farrar’, a novel by Josephine Tey, which had lain unfilmed in Hammer's bottom drawer since 1954. Even made over as Paranoiac, Hammer's film of Tey’s novel would be shelved for eighteen months on its completion.

Paranoiac was the directorial debut at Bray of lighting cameraman Freddie Francis, whose elegant lensing had graced the likes of Sons and Lovers and, more recently, The Innocents. Unusually for Hammer, Francis was now the fifth director that Reed had worked for inside the space of three years.

‘Directors don't register too much with me; I just get on and do my job. Freddie Francis was a great technician. He was really a lighting cameraman and he was a very nice fellow. Terry [Fisher] didn't know half that stuff, but I think Terry was more artistic. They used to revamp the sets and go from film to film, and Terry knew exactly where to put the camera, quickly. I don't really have an opinion on John Gilling, except that he was very brash and forthright and unpopular with a lot of people.

‘I did The Scarlet Blade with Gilling, and that ridiculous film, The Brigand of Kandahar. I saw him again in Spain just before he died; it was he who tried to get Colin Garde to put a chest-wig on me for The Brigand of Kandahar - this blue-eyed, turbaned Turk with a chest-wig on! It looked so ridiculous that they had to reshoot the sword-fight without the chest-wig. That was the last one and then I called it a day, because I could see I had learned enough from Hammer by then.’

The Scarlet Blade, another revamp of an old property (King Charles and the Roundheads this time, which had originally been abandoned with the company's 'race into space' after making The Quatermass Xperiment in 1954), and The Brigand of Kandahar, both of which were shot in 1963, represented Reed's swan-songs. Even in The Brigand of Kandahar, Hammer never quite elevated Reed to star-status, but he is unreserved in his praise for the way in which the company helped to launch his subsequent career. ‘They taught me my craft, Hammer..’ It would ultimately be left to producer-director Michael Winner to put the Reed name above the title of a film in the credits.

‘One was conscious at that time of getting a certain 'following,' and I was wary of being involved with Hammer any longer if it was going to typecast me. Christopher was getting worried; not Peter Cushing - but Christopher was, and he used to warn me about it. All the Hammer films were pretty good, so they were distributed by Rank or ABC, and I think ABC eventually said, 'we'll do a deal and show your films at our cinemas provided you use our facilities,' and the wonderful homeliness of Hammer films at Bray was put into the 'factory' of ABPC at Elstree [where The Brigand of Kandahar was shot], and it wasn't the same. I thought: this is not Hammer anymore - this is not the family anymore.. I want out.’

Reed's wish was granted, but not in the way he expected. A brawl in the Carzy Elephant night-club, after filming The System for Michael Winner in 1964, left his face severely scarred and his blossoming film career temporarily in tatters.

‘I did the Winner film, The System, and then I was driving minicabs: nobody would employ me because my face was all scarred. Suddenly Ken Russell was making films for the BBC and he said he wanted to see me. So I went up to see him at Lime Grove and he told me he was making a film about the composer Debussy [’The Debussy Film’] - did I know who he was? I said no. He told me, and asked me if I wanted to do it. I said, what about my face? And he said, 'What about your face..?’ Next thing I knew, I was on the front cover of the Radio Times and people began to accept me, not just as the werewolf, but as somebody who made 'art' films. Then I did Rossetti [’Dante's Inferno’] and Henri Rousseau, and after that, of course, Women in Love and The Devils. He's a good man, Russell.’

Reed also made other films with Michael Winner between the years 1965 to 1968, and by taking heed of Christopher Lee's early warnings over typecasting, he rose to become the biggest star ever to spring from the Hammer stable. Lee may have gone on to make more films in number - around 250 at present count, almost qualifying for an entry in the Guinness Book of Records! - but precious few of them were of the calibre of Women in Love, the universal appeal of Tommy, or [until the 1990s] produced on the scale of The Assassination Bureau and Royal Flash. Hammer's highest-ranking stars did share the acting honours in Richard Lester's various romps with The Three Musketeers, however.

But while Lee's career had continued unabated into the present day (in numerical terms, at least), Oliver Reed's had gone into something of a self-perpetuating decline.

‘I've done a lot of films for a man whom nobody ever works for - but I do - called Harry Alan Towers.’ [Towers was responsible for Lee's Count Dracula in 1970, as well as his series of Fu Manchu pot-boilers; among his more recent efforts has been The Mummy Lives with Tony Curtis.] ‘Harry has been as loyal as loyal to me through the years, and I'm as loyal as loyal to him. He's always coming up with ideas; he's a super little fellow. He has offices in Toronto, and a few years back, he had this deal in South Africa: I made about five films back-to-back over there. Lots of people went there, who might not want to be named, but Johannesburg, at one time (where most of us lived), was like walking round Twentieth Century Fox, there were so many films going on over there. Then the government closed down the tax-breaks and no more films were made in South Africa..’

We had just about covered as much as memory would allow and I had got all the material I wanted. It was time to wind things up. What did he think the future now held for him? I concluded by asking him.

Reed looked wistful. ‘I'm not quite sure I'm that interested in acting any more, to tell you the truth. If I think something is going to be fun, then I'll do it, but unless I get really bored, I don't know that I'm going to go charging around all over the place any more..’

From the way he said this, it was clear that Oliver Reed thought the best of it was over. Our interview certainly was, and all that remained for me to do was to thank him for his time and ask him if he would sign a copy of the script of The Curse of the Werewolf, which I had brought with me for just such a purpose.

Oliver obliged, and made to take his leave with Jacko in tow.

‘Now you can take your wife to the ‘Big Tomato’’, he suggested. ‘In Guernsey, we call St Peter Port the Big Tomato..’ (St Peter Port is the capital of Guernsey, and the island is famed for tomato production due to its temperate climate.) ‘Or go into the country, to the south. There are some very pretty places there..’

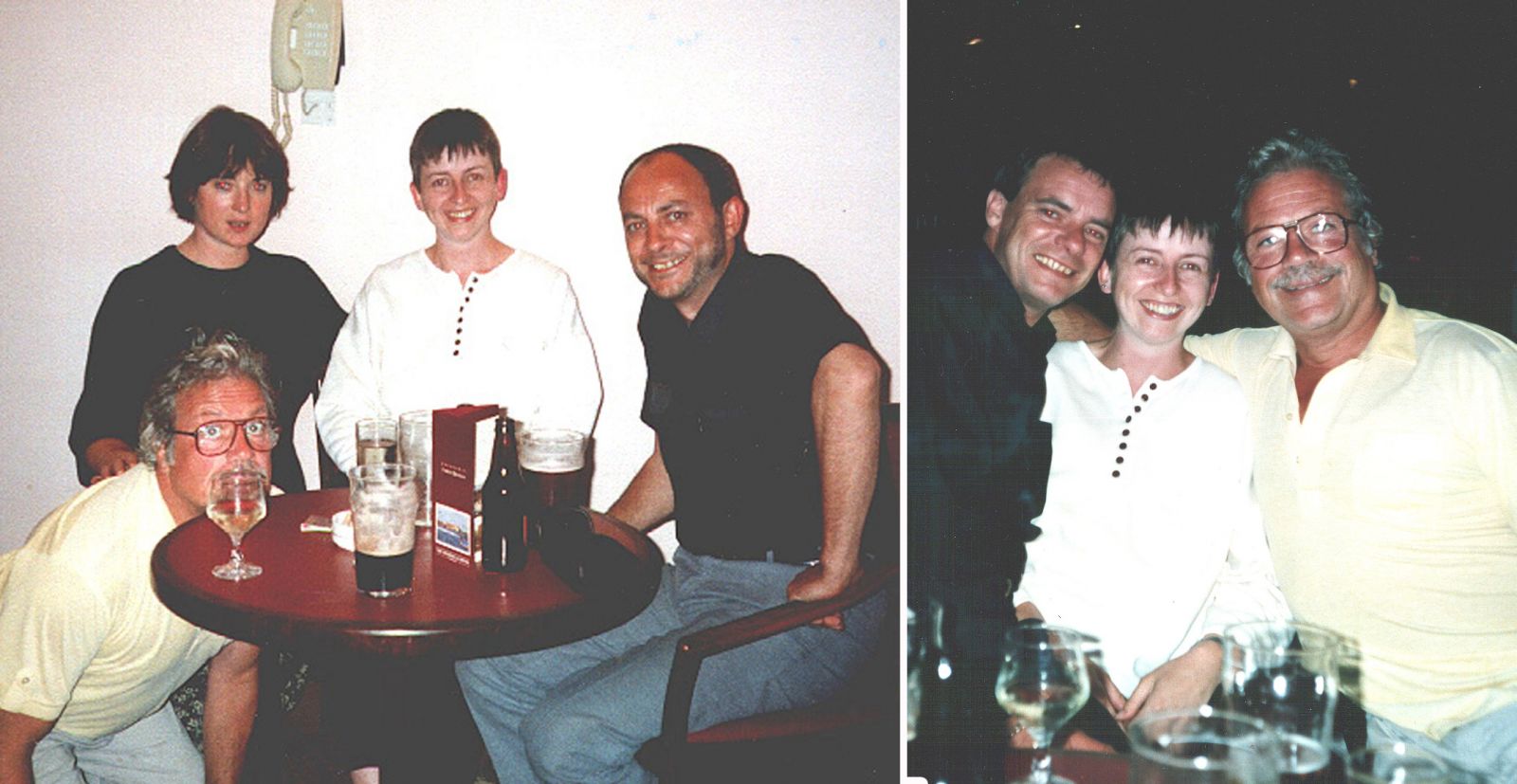

As we walked towards the hotel lobby, an idea struck me. Jane and I were marooned on Guernsey for another night, with nothing much to do and no particular place to go. ‘Before we leave the island, and if you’re free, could I buy you and your wife a drink?’ I asked. He barely gave the proposition pause for thought. ‘Yes, of course!’ he gleefully replied. ‘Why don’t we meet you here at seven.’

‘I’ll look forward to it,’ I said, and thanked him again.. little realising what fate now awaited us.

It was just on 7 when Oliver and Josephine Reed, accompanied by the ever-present Jacko, joined my wife and myself in the lounge of the Peninsula Hotel. But with them came a disturbing air, as though all of us had inadvertently woken to find ourselves in the middle of a film by David Lynch. It was tangible and immediate, and it set hackles rising.

It was plain to me from the outset that something about Oliver Reed had changed in the interval between noon and evening. It did not take long to figure out what had brought about that change: whereas Jane and I had spent the afternoon exploring the avenues and alleyways of the ‘Big Tomato’, Reed had spent it carrying on where we had left off in the drinking stakes earlier in the day. When we met for a second time, the moon was high in the sky, and Oliver was already in the process of turning into ‘Ollie’ - rake-hell and roustabout, scourge of hotel bars.

I checked on the sturdiness of the surrounding furniture, and having satisfied myself on that score, I set about ordering some drinks. Oliver immediately buttonholed me and gave me a copy of the press-book for Paranoiac, which he had taken the time to rescue from a suitcase full of memorabilia. ‘I like you,’ he said, handing me the gift. ‘I don’t know why, but I like you.’ I thanked him and turned to the bar, still uncertain of the general situation. It was my first mistake.

I checked on the sturdiness of the surrounding furniture, and having satisfied myself on that score, I set about ordering some drinks. Oliver immediately buttonholed me and gave me a copy of the press-book for Paranoiac, which he had taken the time to rescue from a suitcase full of memorabilia. ‘I like you,’ he said, handing me the gift. ‘I don’t know why, but I like you.’ I thanked him and turned to the bar, still uncertain of the general situation. It was my first mistake.

Having seated ourselves in a wide circle around a table adjacent to the bar, my first task was to find a common language. Hammer sprang naturally to mind, with the attractions of Guernsey providing a fallback position. I opened with some questions of a more specific nature than the formal interview had allowed for. Second mistake.

His animal senses heightened, Oliver was alert to every nuance that he thought he could detect in the conversation. ‘You were perfectly all right this morning; now you’re acting like a BLOODY POLICEMAN!’ he bawled across the table at me, stunning the rest of the party to silence with the suddenness of the onslaught.

‘I didn’t mean to be,’ I said, parrying the accusation with an attempt to explain away what in any other context would have been taken as a straightforward enquiry. I have been here before, I thought (and as the real Rossetti had written), and the best defence against any suspicions induced by drink was not to query, but to indulge in small-talk until the drinker himself raised a subject which could be pursued, as Oliver very soon did.

Pacified by the rapt attention of those around him - all of whom were now subdued to a state of reverence, for fear of offending him further - he embarked on a series of conspiracy theories in relation to the way that Hammer had plied its trade. I took mental note, paid lip-service to the more curious claims, and tried my level best to keep the beast from sniffing blood and striking out again with an enraged claw.

The problem with alcoholics and their mood-swings is that you can never see them coming. You can never know exactly when the effects of the drink - or the years of drinking - are actually going to kick in. In Oliver’s case, the first - loud, aggressive, sentient, volatile - stage had evidently kicked in during our absence from him. The second - violent, bullying, self-loathing - stage was still to come.

Anecdotes about the man he referred to as the ‘old Colonel’, Jimmy Carreras - ‘All he wanted to do was pump up the leading ladies. I was doing The Trap in Vancouver and learned he was in town. I called him up to ask if he wanted to meet me for a drink. He said he was busy on top of a large-bosomed lady and could we do it later in the evening. I didn’t call back because it was obvious that he was more interested in the birds than in me’ - were punctuated by pauses for more and sillier photographs until a gentle reminder from Josephine about his next port of call ignited a flash of venom and produced the bald rebuke: ‘--Can you imagine being MARRIED to it..?’

Again, the moment passed; the moon went behind a cloud.

Throughout all this, Josephine Reed had sat passively by her errant husband’s side - at times solemn and embarrassed, at others, putting a brave face on things with those little politenesses of conversation that attempt to pretend that none of what is clearly happening around one is actually happening at all.

At nine o’clock, the Reeds rose to leave; Oliver was due at the local pub, to watch his pool team in action. He invited us to come and watch him play cricket at a charity event on the mainland the following week. I said I would think about it. (I thought about it and decided on balance not to go.) But having already waded thus far into his ‘cups’ with him, I also decided that I might as well go all the way, there and then, to see just how deep these waters ran.

Josephine agreed to us tagging along, and ‘all the way’ took us next to the Wayside Tavern, a bustling country inn, where a well-supported pool tournament was currently in progress.

Oliver stationed himself at a pillar near the bar, while Josephine was shown to a table nearby. By now, Oliver was betraying all the signs of the habitual heavy drinker: the bemused air, thinly-veiled aggression, and the macho posturing with which he appeared to feel increasingly comfortable. ‘What’s he got that I haven’t?’ he demanded of my wife, towering above her until a reply was forthcoming. Jane, who was three months pregnant at this time, was feeling increasingly uncomfortable in his presence, sensing the danger that Reed’s sister-in-law, Micky (wife of his older brother David), considered to be a feature of the man: ‘He was a frightening man -- very frightening.’

Most of the earlier politeness and all of the charm had vanished in a sea of lager and gin. Even Josephine, infected with a similar paranoia, began to imagine sleights where none existed: I was harangued for not showing enough appreciation when her husband had earlier presented me with the press-book for Paranoiac.

There was no doubting that Josephine was immensely protective of her wayward charge, and thoroughly devoted to him. But that devotion appeared to embrace the notion of indulging him in his waywardness. In his present mood, Oliver required to be appeased, pandered to, and obeyed. The consequences of failing to do so risked a wrath that was more than capable of sweeping all before it, regardless of the cost - for despite the decline in his fortunes, he still had the wherewithal to pick up any tab for damages that ‘Ollie’ might incur in his wake.

Jacko hovered steadfastly on the periphery of it all, taking requests for drinks, organising payment, allocating the rounds; an ex-merchant seaman, he was a darker horse than he gave the impression of being and I was not quite sure if he was amused by Reed, or at him. Money was spread across the bar in small piles of crumpled notes, as though someone had upended the waste-bin of a forger and disgorged all the misprints. No one cared - everyone was drinking on Oliver’s account. But when time was up at the Wayside Tavern, it was ‘Ollie’ who heard the call. And now it was back to Ollie’s place.

Five of us had arrived at the pub, but when we left it again, that tally had risen to seven. Somewhere along the way, another two lost souls had joined the hay-ride.

When we arrived back at the Reed manse - a large but unassuming house set behind wrought-iron gates - we all filed up to ‘Oliver’s Bar’, a first-floor fun room, separate from the house, and sited atop a double garage. It was called Oliver’s Bar, but Ollie was now in charge - Oliver having been well and truly consigned to limbo while the beast lorded it over the proceedings for the duration of his stay, which at this point in time, looked likely to be all night.

Jane and I had already agreed that enough would soon be enough; we would acquaint ourselves briefly with the place, say our goodbyes, and retire gratefully to bed. So much for the theory. The welcome was warm, more drinks were proffered, a rock-and-roll tape was relayed to the sound system, and a party atmosphere soon prevailed. Josephine and Jane nestled for a quiet chat on one of several sofas that were set around the perimeter of the room, and I found myself a seat at the bar.

While Ollie set about attending to the others, I took the opportunity to look around. At the far end of the narrow room, directly opposite the bar, hung a framed blow-up from The Devils. It was a huge portrait of Reed as the tousle-haired Urbain Grandier, turbulent priest of Loudun, attired in his golden robes. The effect of that portrait, with its solemn, magisterial stare, was literally hypnotic - so much so, that I was moved to express my admiration of it to Ollie.

He nodded approvingly at the imposing image of his younger self. ‘I was pretty in those days,’ he said. Josephine’s gaze had also turned to the picture. ‘That was why I married him,’ she concurred.

Once again, he appeared to have mellowed some and was able to engage in disjointed but civil conversation for a time. It was only after I had excused myself from his company, for a brief spin around the floor with Jane to a favoured track, that there came the eruption which had been threatening since we had met at the hotel.

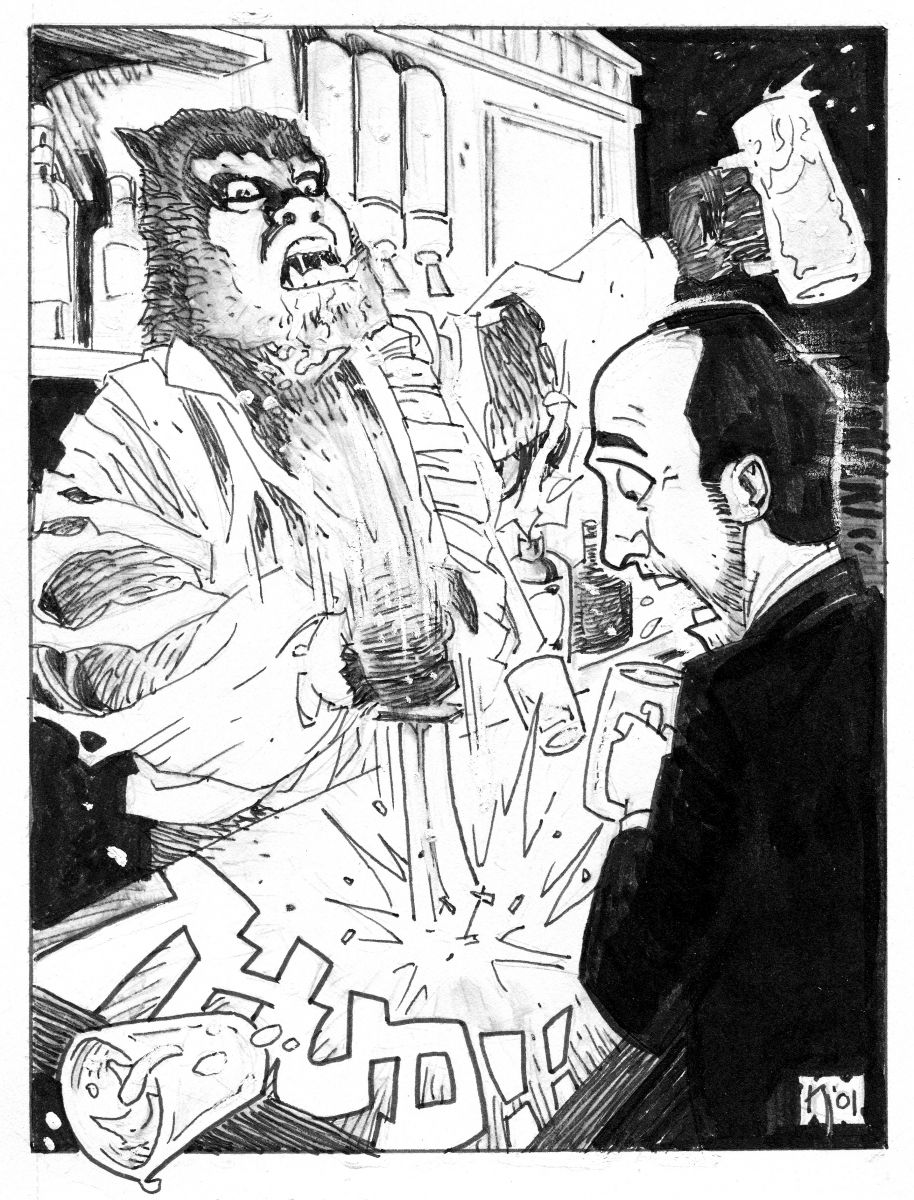

When I reclaimed my place at the bar, I could see immediately that the metamorphosis from man into animal was now complete. Ollie had regressed to the persona of his days spent in National Service, and he stood wild-eyed and saluting madly, clicking his heels, and barking out name, rank, and serial number. ‘Reed...Oliver...SAH!’

I leaned on the bar and looked at him, not knowing whether to laugh at the pose or pay it homage. Before I had time to choose, he reached under the bar.

A hand was raised on high - something glinted in the light - and the tip of a wicked-looking hunting knife slammed into the wooden bar-top, mere inches away from my forearm.

I lifted my gaze from the knife, still clutched tightly in Ollie’s vicelike grip, and our eyes met. His were hard and unblinking. Instinctively, I decided that mine should be the same.

Courage did not come into it: too much alcohol had passed into my bloodstream between seven o’clock in the evening and two o’clock in the morning for me to feel frightened or even threatened by this action. He had made his move, and all I could do was wait and see what his next move would now be.

The noise of the knife thudding into the bar had turned all heads in our direction, and silence reigned. We stared at each other for a long time - what, in Ollie’s world, might have amounted to ‘sizing each other up’. The outburst of violence, albeit directed against the bar, had been so sudden, so unexpected, that no other course of action was open to me, and there was nothing for anyone else to do but wait.

In another moment, it was over - for the time being. Ollie extracted the knife from the bar-top and laid it aside, still within too-easy reach, before picking up where he had left off. The hubbub of voices swelled to its former volume, and the semblance of normality was restored.

This is not to boast that I had faced him down, but I had faced down the attempt to humiliate me and to show me up as a lesser mortal than himself - as seemed to be his way with those around him on occasions like this. Ollie, for his part, reverted to cavorting around and bellowing indecipherably, as he had been doing before he was caught in the light of the moon, and just as though nothing untoward had taken place in the meanwhile.

He had blinked first, but he was to have his revenge.

The sound of a dull thud meant that one of our companions had now fallen off his stool onto the floor, for the second time inside of an hour. He was helped to his feet - again - but the event seemed to indicate to Ollie that something more lively was called for to spice up the flagging proceedings; we were to be subjected to the ritual of the ‘singing-box’ - an antique ottoman to the side of the room, into which the participants in the game were enclosed, and from where they sang or recited some ‘ditty’ until he was content to let them out again. This Ollie adjudicated by sitting on top of the box while they performed. When my turn came, the only thing I could think of was ‘My Bonnie’. It appeared to satisfy the requirement, but not particularly to amuse our host, and at this time of the morning, our host required to be amused above all.

By the time I had been liberated from the claustrophobic clutches of the singing-box, the two other inhabitants of Oliver’s Bar were slumped against it, on the floor. Only he, Jacko, and I remained standing - with Josephine now departed, and Jane sitting alone nearby.

I returned to my seat at the bar, but no sooner had I recovered my composure than - horror of horrors! - my wife yawned. (In deference to our unborn child, Jane had been abstinent for most of the evening and was naturally tired.) What made matters worse was that Ollie saw her. Third, and last, mistake.

Before I knew what was happening, I was frog-marched to the door and ordered to ‘take her home!’

For the moment, I remained unaware of the circumstances that were inspiring such an untimely and graceless exit. (Jane was to explain all on our way back to the hotel). I thanked him for his hospitality and told him it had been a pleasure to meet him. The beast merely growled.

‘You can come back...but take her home,’ he ordered again, and we were summarily ejected from the room - I, by the seat of my pants! ‘I thought he was going to throw us both down the stairs,’ Jane confided, as we made our impromptu exit.

The loyal Jacko was profuse in his apologies. ‘He’s not usually like this - I don’t know what’s the matter with him,’ he said, as he sought to escort us off the premises with a modicum of decorum. It had the ring of special pleading, and it sounded like the automatic reflex of one who had been given ample opportunity to learn his lines.

Tell that to all the publicans, including several in St Peterport, who’d had occasion to bar Ollie from their premises, I thought, as I reassured Jacko that no offence had been taken. In retrospect, I figured that he already had.

I need only add that I did not go back. By that time, I had seen quite enough of Ollie Reed in action.

As for the cricket match, the whole affair turned out to be another in an embarrassingly long list of shambolic public appearances: Ollie had turned up ragged and drunk, was bowled out first wicket, and became embroiled in a punch-up with a journalist. His presence had brought the event to the attention of the press - as the organisers presumably intended - but the resultant publicity was surely not what they originally had in mind. A couple of chaotic television spots followed, including a dangerous stunt performed on him by Channel 4’s The Word, whereby he was surreptitiously filmed in his dressing-room prior to making his appearance on the show. The candid footage was screened to him as he guested, to see his reaction as he watched his own pathetic image stumbling into furniture and talking to itself in stupefied bewilderment. During the course of this bear-baiting spectacle, I half-expected him to rip host Terry Christian’s head from his shoulders in front of two million startled viewers. He managed to refrain - even in that darkest of many dark hours, Oliver Reed showed a remarkable power of restraint over the beast within - but to my mind, he came awfully close.

After that, it was all downhill. What remained of the public’s prurient interest in one of the great wonders of the drinking world finally waned. He upped and moved again. To Ireland, this time, and a small village called Churchtown, in County Cork. In February, 1995, he was thrown off the multi-million dollar Geena Davis pirate epic Cutthroat Island - so by then, even the much-vaunted Reed professionalism could no longer be relied upon to save the day.

The death of Reed’s long-time agent, Dennis Selinger, in February, 1998, merely reinforced the view that he had already divulged to me in the course of our interview. He announced to the press that he was to retire from acting. ‘It’s time to slow down...and grow old gracefully,’ he reportedly said. ‘Time to call it a day.’

A bout of rehabilitation followed, complete with photo-shoot of Reed and wife strolling in Irish pastures, having found peace and tranquillity at last. It seemed to do the trick. By 1999 - all thoughts of retirement forgotten - he had been cast as Proximo in Ridley Scott’s Gladiator and was being lined up to play the title character in a prestigious television adaptation of Sheridan Le Fanu’s Uncle Silas. All the signs were there of a rehabilitated career, as well. But it was not to be.

Oliver Reed raised the curtain on his personal hell for the last time on Sunday May 2, 1999, in ‘The Pub’ - a small port-side bar in Valletta, capital of the island of Malta. It was here, during a break in the filming of Gladiator, that he drank himself to death - or as near as a fatal heart attack after ingesting a huge quantity of rum, beer, and scotch comes to complying with that definition. ‘Ollie’ had finally ended the career of Oliver, as surely as Mr Hyde poisoned Dr Jekyll as well as himself, and just as that career was poised to take off again. The beast had done for his better half at last, as he had been trying to do ever since he was brought into being.

Oliver Reed raised the curtain on his personal hell for the last time on Sunday May 2, 1999, in ‘The Pub’ - a small port-side bar in Valletta, capital of the island of Malta. It was here, during a break in the filming of Gladiator, that he drank himself to death - or as near as a fatal heart attack after ingesting a huge quantity of rum, beer, and scotch comes to complying with that definition. ‘Ollie’ had finally ended the career of Oliver, as surely as Mr Hyde poisoned Dr Jekyll as well as himself, and just as that career was poised to take off again. The beast had done for his better half at last, as he had been trying to do ever since he was brought into being.

Reed had his apologists, of course - Michael Winner (apologist for the entire industry, as often as not, when he’s called upon to provide a quote), Glenda Jackson, and others whose dealings with him had been few and far between since his heyday in the sixties and seventies. But having delivered the obligatory tribute, Winner was more forthcoming: ‘There was no greater pendulum swing in any human being that I’ve ever met than Oliver Reed sober to Oliver Reed drunk. If you look at Oliver’s career as the career of an artist - of an actor - it went down the toilet.. It basically vanished,’ he acknowledged.

It is reasonable to say of the Reed of latter days that he died as he would have wished. A younger Reed might have preferred it otherwise - he might have preferred to have died in bed. But that Reed was long gone in more ways than one, and for all his apologists, he was unlikely ever to have returned.

Oliver Reed’s death was not a dramatic, glorious, or even romantic finale - it was a sad, inglorious, ignominious, and entirely predictable end. In fact, it could have been predicted by anyone who knew him for most of the last half of his life.

The man I met in 1992 was no jovial, fun-loving, one-of-the-boys, as his contemporaries like to have it. He was alcoholic, pure and simple - and he had probably been alcoholic since the middle of the seventies, when a youthful ability to live with a regular intake of huge quantities of drink changed imperceptibly into a middle-aged inability to live without it. Ollie was not a figure of fun, as much of the media and many of his show business ‘chums’ often sought to imply. He was a tragic figure, who destroyed himself utterly.

As a man and an artist, Oliver Reed had many admirable qualities: he had little time for the shallow world of celebrity stardom, preferring the company of old friends and confidantes from outside the business. At the height of his fame, he steadfastly refused to leave Britain and head off to Hollywood to further his career, as he was strongly advised to do. He saw that as cynical manoeuvring, and opted instead for the tax penalty of staying put. It cost him Broom Hall.

Thanks to the miracle of modern technology, Oliver Reed’s films will outlast the headlines around which much of his later career revolved; his legacy to world cinema, and to the world of horror, remains intact - not least through his performance as the tormented Leon in Hammer's The Curse of the Werewolf.

‘When I look at The Werewolf,’ he said to me in one aside, ‘I think I did fine.’

You did, Oliver. You did indeed.

And I must say that it was an experience. One for the storehouse of anecdotes. But the abiding memory of it all was not our treatment at the hands of Ollie the belligerent buffoon - it was of the framed blow-up of Reed as Grandier, that presided majestically over Oliver’s Bar.

There is a scene in Ken Russell’s television film on the life of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, where the artist sits brooding in a chair. That is how I see Oliver Reed: sitting in his bar in the wee small hours and staring at that picture hanging in the warning shadows, at the opposite end of the room. The Picture of Dorian Gray in reverse - where youth and beauty were transferred to the image, and the cumulative result of all the sins was made manifest in the flesh.

Oliver Reed had been a magnificent animal. And in that picture, he looked like a god..

But in the film business, there are no gods. Only monsters.

.........................................................................................................

OLIVER REED: A PRODUCER'S TALE

‘Oliver's actually a very good actor - technically he's superb. I had Ollie and Richard Widmark together on The Sellout in 1974 (which was directed by Peter Collinson), and one evening, he asked a few of us to come and have a drink with him in his hotel. Richard wouldn't go, so the rest of us went up to his suite on the top floor. It was about eight o'clock in the evening and there were six of us, and we were going off afterwards to have something to eat. Ollie had asked for the drinks to be sent up, and when the waiter brought the drinks, he also brought the bill for signing. Ollie saw how much it was and said, 'I'm not paying that!' and I thought - whoops, this is going to be a short evening: one drink and goodbye! But Ollie rang his driver from the bedroom, and fifteen minutes later, in came the driver with eight 'flunkies' behind him, each of whom carried a box. He had gone out and bought eight boxes of booze.. And it wasn't just wine; it was spirits - the place was like a pub! When we woke up next morning, still in Ollie's suite, half the boxes were empty and Ollie had drunk as much as the rest of us put together! He hadn't been to sleep. And he went straight onto the set and into make-up - eight o'clock in the morning - stone-cold sober. I don't know how he does it.. He is unbelievable.’

--Tom Sachs, one-time production manager for Hammer, speaking in 1993

I checked on the sturdiness of the surrounding furniture, and having satisfied myself on that score, I set about ordering some drinks. Oliver immediately buttonholed me and gave me a copy of the press-book for Paranoiac, which he had taken the time to rescue from a suitcase full of memorabilia. ‘I like you,’ he said, handing me the gift. ‘I don’t know why, but I like you.’ I thanked him and turned to the bar, still uncertain of the general situation. It was my first mistake.

I checked on the sturdiness of the surrounding furniture, and having satisfied myself on that score, I set about ordering some drinks. Oliver immediately buttonholed me and gave me a copy of the press-book for Paranoiac, which he had taken the time to rescue from a suitcase full of memorabilia. ‘I like you,’ he said, handing me the gift. ‘I don’t know why, but I like you.’ I thanked him and turned to the bar, still uncertain of the general situation. It was my first mistake.

Oliver Reed raised the curtain on his personal hell for the last time on Sunday May 2, 1999, in ‘The Pub’ - a small port-side bar in Valletta, capital of the island of Malta. It was here, during a break in the filming of Gladiator, that he drank himself to death - or as near as a fatal heart attack after ingesting a huge quantity of rum, beer, and scotch comes to complying with that definition. ‘Ollie’ had finally ended the career of Oliver, as surely as Mr Hyde poisoned Dr Jekyll as well as himself, and just as that career was poised to take off again. The beast had done for his better half at last, as he had been trying to do ever since he was brought into being.

Oliver Reed raised the curtain on his personal hell for the last time on Sunday May 2, 1999, in ‘The Pub’ - a small port-side bar in Valletta, capital of the island of Malta. It was here, during a break in the filming of Gladiator, that he drank himself to death - or as near as a fatal heart attack after ingesting a huge quantity of rum, beer, and scotch comes to complying with that definition. ‘Ollie’ had finally ended the career of Oliver, as surely as Mr Hyde poisoned Dr Jekyll as well as himself, and just as that career was poised to take off again. The beast had done for his better half at last, as he had been trying to do ever since he was brought into being.