De Mille’s Samson and Delilah (1949) revived the genre for post-war audiences, but its stage-bound sets exposed the limitations of trying to mount a story on so vast a scale within the confines of a lot as big as even that of Paramount. Nevertheless, the film was the most commercially successful of its year and it encouraged the major studios to go for more of the same – but without the increasing overhead costs which were fast becoming a fact of Hollywood life; the practice of shooting on a cheaper basis abroad took hold, and so-called ‘runaway’ production came into being – the first and most extravagant example of which was M-G-M’s monumental Quo Vadis (1951).

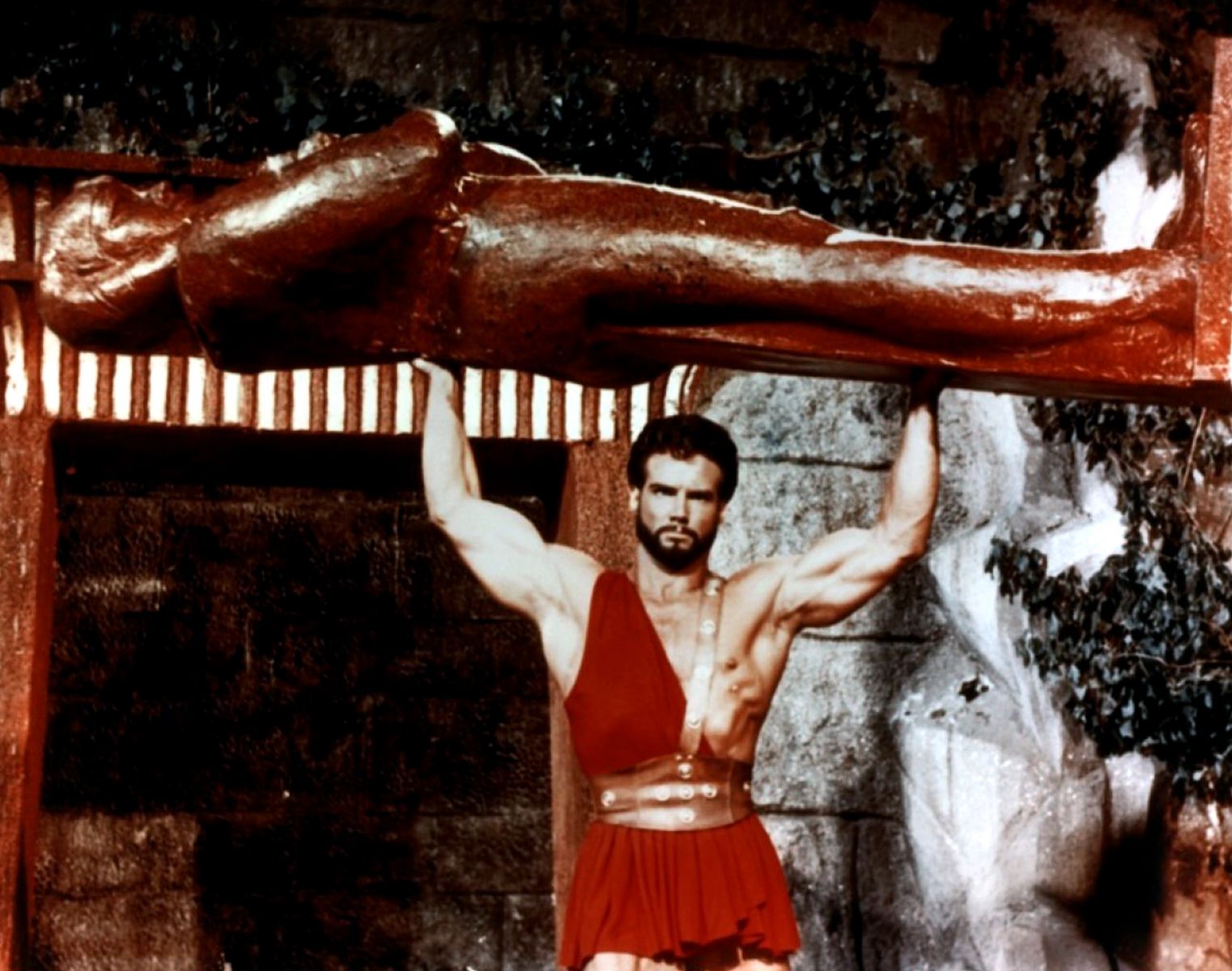

De Mille’s Samson and Delilah (1949) revived the genre for post-war audiences, but its stage-bound sets exposed the limitations of trying to mount a story on so vast a scale within the confines of a lot as big as even that of Paramount. Nevertheless, the film was the most commercially successful of its year and it encouraged the major studios to go for more of the same – but without the increasing overhead costs which were fast becoming a fact of Hollywood life; the practice of shooting on a cheaper basis abroad took hold, and so-called ‘runaway’ production came into being – the first and most extravagant example of which was M-G-M’s monumental Quo Vadis (1951). So staggeringly successful was Hercules Unchained in release in the summer of 1960 that film companies fell over themselves to buy up Italian epics of any style or substance. As it happened, Reeves had been far from idle in the period immediately preceding the Warner Bros US/UK release of Hercules Unchained; by the end of 1959, he had completed a further three features: The White Warrior (Agi Murad il diavolo bianco), The Giant of Marathon (La battaglia di Maratona) and The Last Days of Pompeii (Gli ultimi giorni di Pompei), all of them initiated in the wake of Hercules and fostered by Reeves’s refusal to repeat the role for Levine and Francisci for a second sequel. In America, Jacques Tourneur’s The Giant of Marathon was released by M-G-M before Hercules Unchained but in Britain, it went out immediately after it, heavily promoted with the longest television ad ever screened for a film; one month later, Mario Bonnard’s The Last Days of Pompeii followed it into the nation’s cinemas. Not only was the genre now in full flood but it was throwing new talents onto the stage of world cinema: cinematographer Mario Bava had shot Hercules Unchained, The White Warrior and The Giant of Marathon, but he had taken over the reins of the last when Tourneur departed prior to its completion and his reward was to be offered his official directorial debut with La masquera del demonio (The Mask of Satan/Black Sunday; 1960); in the same vein, most of The Last Days of Pompeii was actually directed by long-time assistant director Sergio Leone, whose work on the film was also rewarded by a first solo effort – The Colossus of Rhodes (Il colosso di Rodi; 1961). As conscious of the threat from without as was Rome itself when faced with the Visigoths, older talents were also keen to embrace the new genre: Stanley Kubrick and Kirk Douglas’s Spartacus (1960) deployed the combined thespian authority of Laurence Olivier, Charles Laughton, Peter Ustinov and Jean Simmons to try to show that CineCitta could never beat Hollywood at its own game. In the event, it had no need to fear.

So staggeringly successful was Hercules Unchained in release in the summer of 1960 that film companies fell over themselves to buy up Italian epics of any style or substance. As it happened, Reeves had been far from idle in the period immediately preceding the Warner Bros US/UK release of Hercules Unchained; by the end of 1959, he had completed a further three features: The White Warrior (Agi Murad il diavolo bianco), The Giant of Marathon (La battaglia di Maratona) and The Last Days of Pompeii (Gli ultimi giorni di Pompei), all of them initiated in the wake of Hercules and fostered by Reeves’s refusal to repeat the role for Levine and Francisci for a second sequel. In America, Jacques Tourneur’s The Giant of Marathon was released by M-G-M before Hercules Unchained but in Britain, it went out immediately after it, heavily promoted with the longest television ad ever screened for a film; one month later, Mario Bonnard’s The Last Days of Pompeii followed it into the nation’s cinemas. Not only was the genre now in full flood but it was throwing new talents onto the stage of world cinema: cinematographer Mario Bava had shot Hercules Unchained, The White Warrior and The Giant of Marathon, but he had taken over the reins of the last when Tourneur departed prior to its completion and his reward was to be offered his official directorial debut with La masquera del demonio (The Mask of Satan/Black Sunday; 1960); in the same vein, most of The Last Days of Pompeii was actually directed by long-time assistant director Sergio Leone, whose work on the film was also rewarded by a first solo effort – The Colossus of Rhodes (Il colosso di Rodi; 1961). As conscious of the threat from without as was Rome itself when faced with the Visigoths, older talents were also keen to embrace the new genre: Stanley Kubrick and Kirk Douglas’s Spartacus (1960) deployed the combined thespian authority of Laurence Olivier, Charles Laughton, Peter Ustinov and Jean Simmons to try to show that CineCitta could never beat Hollywood at its own game. In the event, it had no need to fear.